News

The Scale of the Problem: Alcohol vs. Opioids, by Jan Gryczynski, PhD

Editor’s note: PGDF’s Advisory Council (AC) is comprised of experts from across the field of addiction. In this series, we invite AC members to share their expertise and experience with PGDF constituents.

Dr. Jan Gryczynski is a Senior Research Scientist at Friends Research Institute. His research interests include the intersection of medical care and behavioral health, particularly with respect to identifying novel approaches to service delivery that improve access, engagement, and outcomes. His health services research in addictions spans the spectrum of substance use problems, from early intervention studies with adolescents, to treatment research with populations characterized by high problem severity and complex comorbidities. Much of his work has emphasized practical strategies for service improvement in vulnerable and underserved populations. His research has included randomized trials of service strategies in addiction treatment, studies to inform intervention design, and investigations of individual and contextual factors that shape health behavior, service delivery practices, and patient outcomes. Adjunctive to these research activities, Dr. Gryczynski maintains an active interest in methodology and quantitative analysis.

**************

In the wake of so much death and tragedy wrought by the opioid epidemic, the issue of opioid addiction has been catapulted to the center of the national consciousness. Opioid addiction is a multi-faceted problem that demands focused attention, better policies, and resources – more of them, allocated wisely.

Given the scale of the opioid problem, it would be appealing for a philanthropic foundation like The Peter G. Dodge Foundation (PGDF) to expand its work into the opioid arena. Instead, PGDF has chosen a different path. While there are many organizations doing great work on addiction issues more broadly, PGDF will continue to focus on alcohol specifically.

This adherence to the foundation’s core issue is commendable. Alcohol still accounts for a tremendous share of the overall societal burdens and costs of substance use. The latest estimates from the National Institutes of Health show that the health care-related costs of alcohol are roughly on par with those of prescription opioids (about $27 billion each), with alcohol incurring much higher costs outside of the healthcare sector.

Of course, it’s not a competition. Addiction to any substance is devastating for individuals and families, with reverberating impacts to communities and the nation as a whole. Even so, from a public health perspective, it is sometimes useful to consider how different substances play out at the population level when it comes to use, addiction, and consequences.

Some of the best data we have available to track substance use patterns comes from the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH). This survey is conducted every year by the US Department of Health and Human Services, and is the source for the government’s official statistics on substance use. It is used to give policymakers, researchers, and the public reliable information on things like substance use prevalence, new onset of use, substance use disorders, and the treatment gap. The survey draws a scientific sample of the U.S. population using a sophisticated sampling frame to ensure representativeness, and applies rigorous methods for improving the accuracy of self-report about substance use behaviors. Most importantly, it draws a massive sample, numbering at around 60 thousand people each year. What light can this data shed on the relative patterning of substance use problems at the population level?

An ongoing project using the NSDUH to characterize substance use epidemiology for different substances can offer some insights. The data come from pooled 2015 and 2016 NSDUH surveys, comprising a sample of 114,043 respondents that generalizes to a population of about 269 million non-institutionalized civilians ages 12 and older living in the US. The survey not only ascertains detailed patterns of use for each substance, but also asks a series of diagnostic questions specific to each substance in order to determine whether the respondent meets criteria for a substance use disorder.1

So how does alcohol compare to opioids? First, it is important to consider that opioids as a drug class can be broken out into heroin and prescription opioids (for our purposes we are considering only non-medical use of prescription opioids, so the numbers do not reflect people with legitimate prescriptions for pain medication unless they report misusing the medication).

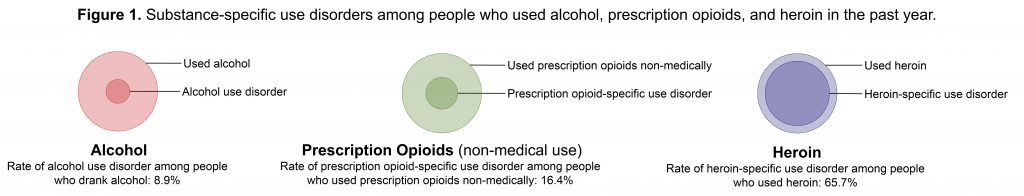

As a proportion of those who used each substance in the past year, the rate of alcohol use disorder was 8.9%, while the rate of opioid use disorder specific to prescription opioids was 16.4%. Not surprisingly, the rate of opioid use disorder specific to heroin was much higher among those who used it, at 65.7%. Put another way, 1 in every 11.3 people who drank alcohol met criteria for alcohol use disorder, compared to 1 in every 6.1 people who used prescription opioids and 1 in every 1.5 people who used heroin. Clearly, the proportion of people who experience problems from their use of substances differs markedly across different substances, and is much higher for opioids than for alcohol. Figure 1 shows a basic visualization of substance use disorders among people who have used alcohol, prescription opioids, and heroin.

Of course, alcohol use itself remains much more pervasive in society. In the past year, about 65.3% of the population reported using alcohol (nearly 175.4 million people), while about 4.5% used prescription opioids non-medically (about 12 million people) and <0.4% used heroin (about 932,000 people). Figure 2 shows the same visualization, but this time it is scaled to the prevalence of each substance in the population. Here the implications of alcohol’s outsized public health burden come into focus. When it comes to the distribution of substance use problems in the population, alcohol takes the lion’s share.

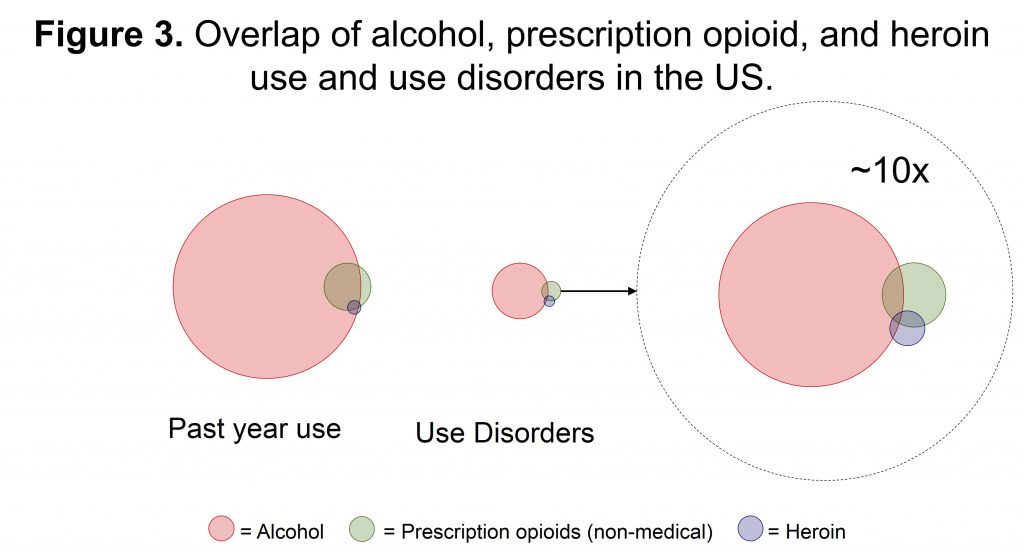

Another important point is that there is considerable overlap in alcohol and opioid use. Figure 3 shows proportional Venn diagrams with alcohol, prescription opioids, and heroin – both with respect to use and substance-specific use disorders. The diagrams are proportional in size to the representation of each substance in the population. At the level of use, there is considerable overlap. Most people who used prescription opioids or heroin also used alcohol. When we zoom in on substance use disorders, we see greater separation, perhaps reflecting the development of distinct preferences for specific substances as use transitions to use disorder. Even here, the overlap is considerable. As any treatment provider knows, polysubstance use and use disorders are quite common among people new to treatment.

Why does all this matter? First, although we all have an intuitive sense that alcohol use and use disorders are more common than for other substances, it helps to quantify and visualize the differences in scale. Second, the relative patterning of substance use problems can inform the development of sound public health strategies and targeted interventions. There are some stark differences in how specific substance use problems manifest across the population. These differences have implications for policy and resource allocation, such as how much to focus on prevention vs. early intervention vs. treatment. They also have implications for how to integrate substance use services into the broader healthcare system, and what kinds of interventions to prioritize.

The field needs organizations that are committed to addressing addiction broadly. Equally indispensable are organizations that focus on specific substances within the addiction issue area. As PGDF grows and continues to make an impact through their philanthropic initiatives, they are poised to play an important role in the alcohol addiction space. It is a space where much work remains to be done. Kudos to PGDF for staying the course.

Notes and Links

Notes:

1 The NSDUH survey still defines substance use disorders according to the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV). For the purposes of this analysis, the term “substance use disorder” refers to DSM-IV abuse or dependence. The 5th edition of the DSM does away with the abuse/ dependence nomenclature in favor of a single spectrum disorder, and also includes other slight changes to criteria (specifically, replacing a criterion of legal problems with one reflecting craving). Although there are some slight differences in the 4th vs. 5th edition definitions as described above, the overall patterning of abstinence, use, and use disorder would likely not change very much under the updated definitions.

Acknowledgements: Benjamin Kussin-Shoptaw contributed to the analysis and the larger project from which the data were drawn.

Links: